The Playhouse (NB) Archaeological Report, Block 29 Building 17AOriginally entitled: "First Theatre Briefing"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1589

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

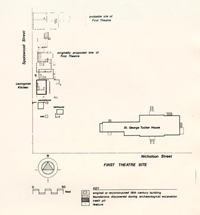

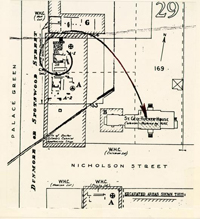

Figure 1. Buildings depicted on the Frenchman's Map, 1782.

Figure 1. Buildings depicted on the Frenchman's Map, 1782.

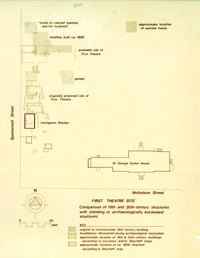

FIRST THEATRE SITE

FIRST THEATRE SITE

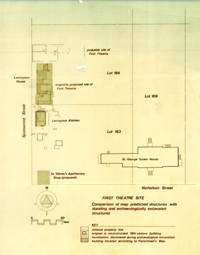

Comparison of map predicted structures with standing and archaeologically excavated structures

Figure 4. Foundations of originally proposed First Theatre site. In the background is the C.M. Hall House, 1931.

Figure 4. Foundations of originally proposed First Theatre site. In the background is the C.M. Hall House, 1931.

Figure 5. Paved cellar and sump pump of originally proposed First Theatre site, 1931.

Figure 5. Paved cellar and sump pump of originally proposed First Theatre site, 1931.

Figure 6. Brick steps leading to the cellar of originally proposed First Theatre site, 1931.

Figure 6. Brick steps leading to the cellar of originally proposed First Theatre site, 1931.

Figure 7. Northern wall of First Theatre foundations uncovered in 1947.

Figure 7. Northern wall of First Theatre foundations uncovered in 1947.

Figure 8. Partition or crosswall, First Theatre foundations uncovered in 1947.

Figure 8. Partition or crosswall, First Theatre foundations uncovered in 1947.

Figure 9. Diagram of the move of Levingston House to form nucleus of St. George Tucker House.

Figure 9. Diagram of the move of Levingston House to form nucleus of St. George Tucker House.

Figure 11. Brick chimney foundation, c. 1800. Uncovered by Noel Hume in 1967.

Figure 11. Brick chimney foundation, c. 1800. Uncovered by Noel Hume in 1967.

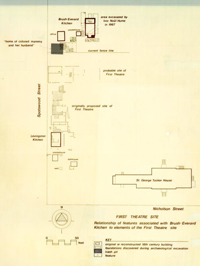

FIRST THEATRE SITE

FIRST THEATRE SITE

Comparison of 19th and 20th Century Structures with standing or archaeologically excavated structures

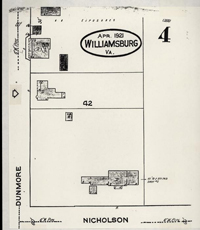

Figure 13. Buildings depicted on the Sanborn Map of 1931.

Figure 13. Buildings depicted on the Sanborn Map of 1931.

Figure 14. Building of "Teahouse" and intersecting crosswalks, 1932.

Figure 14. Building of "Teahouse" and intersecting crosswalks, 1932.

FIRST THEATRE BRIEFING

Office of Excavation and Conservation

Department of Archaeology

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

May 1986

FIRST THEATRE SITE

(Block 29, Area G, Northwest Corner of Colonial Lot 164)

Site History

The history of the site of the First Theatre seems to begin with the purchase of three lots by William Levingston. A merchant from New Kent County, Levingston had previously opened a "peripatetic dancing school" in addition to his mercantile activities (Rankin 1955: 22). In 1716 he petitioned for the use of a room at the College of William and Mary for the conducting of dancing classes in Williamsburg and on March 26 was granted "use of the lower Room at the South end of the Colledge for teaching the scholars and others to dance until his own dancing school in Williamsburg be finished." (Virginia Magazine of History 1896: 169).

Sometime between March and July, 1716, Levingston reached an agreement with his indentured servant and dance master, Charles Stagg, to build a theatre "at his own proper Costs and Charge in ye City of Wmsburgh for Acting Such Plays as shall be thought fitt to be Acted there." By November 1716 Levingston also had "at his own proper Cost and Charge sent to England for Actors and Musicians for ye better performaces of ye sd Plays." (Rankin 1955: 24-25).

Three lots, Numbers 163, 164, and 169, were acquired by Levingston on November 4 and 5, 1716 from the Trustees of the city. Lots 163 and 164 bordered the Palace Green, while Lot 169 lay directly behind them facing Nicholson Street. The agreement stipulated that Levingston must finish within two years the construction of a house upon each of these lots or forfeit their ownership. Also required was the payment of forty-five shillings to the Trustees and if demanded, a "Yearly rent of one grain of Indian Corn." (Stephenson 1946: 2) . As the lots continued in Levingston's possession after the two year period designated, it can be assumed that he built upon them by November 5, 1718.

It seems that the Playhouse must have actually been built earlier in that year, for on June 24, 1718 Governor Spotswood complained to the Board of Trade that he had given an entertainment for the King's Birthday on the 28th of May and "eight Counsellors would neither come to my House nor go to the Play w'ch was Acted on that occasion."

By May 19, 1721, it can definitely be asserted that the Playhouse had been erected, for at that time Levingston mortgaged 2 to Archibald Blair five lots (Numbers 163, 164, 169, 176 and 177) "together with ye bowling green, ye dwelling house, kitchen and playhouse, and all ye other houses outhouses and stables &c thereon" for a period of five hundred years (Stephenson 1946: 3). The Reverend Hugh Jones, professor of Mathematics at William and Mary noted in his sketch of Williamsburg in The Present State of Virginia in 1722, "Not far from hence (Bruton Parish Church and James City Courthouse) is a large area for a Market Place, near which is a Play House and good Bowling Green." (Land 1948: 362).

Little is known of the actual productions and operations of the theatre. As there was no newspaper prior to 1736 in Virginia to give notice of any performances, there is little chance for evidence to document any such activities (Stephenson 1946: 4). It does seem clear, however, that Levingston's venture was not a financial success, for in 1727 Levingston is found in Spotsylvania County, having lost his Williamsburg land.

Lots 163, 164, and 169 were conveyed on February 20, 1735 to George Gilmer by John Blair, executor of Archibald Blair for the remainder of the five hundred years of the mortgage (Stephenson 1946: 5). These were described as " The lotts and land whereon the Bowling Green was, and the Dwelling House and kitchen of William Levingston, and the House called the Play House" (Stephenson, 1947: 1). In autumn of 1736 the playhouse was apparently used by College students for several performances. The Virginia Gazette of September 10, 1736 advertised the performance of The Tragedy of Cato, as well as several comedies on the following week (Stephenson 1946: 5).

There are no records concerning the use of the Playhouse between September 1736 and December 1745. Before December 4, 1745, George Gilmer had conveyed the playhouse and six feet of ground adjoining it to a group of subscribers. The Corporation of the city of Williamsburg, the mayor, recorder, and aldermen petitioned the "Gentlemen Subscribers of the play House in the City of Williamsburgh" to bestow on them the "present useless house on this Corporation" to be used as a public building in which common halls and courts of hustings might be held. The petition argued that the corporation had no building of its own and had been using the James City County courthouse "on Curtesie". It further noted that "the Play House stands in a convenient Place for such Uses; and has not been put to any Use for several Years, and is now going to decay." (Stephenson 1946: 7).

On December 4, 1735, the "Gentleman Subscribers" gave their "shares and interests in the Play-House" to the Corporation. On December 19 the Virginia Gazette advertised for "proposals" on the renovation of the old playhouse. 3

"The Play-House in Williamsburg, being by Order of the Common-Hall of the said City, to be fitted up for a Court-House, with the necessary Alterations and Repairs; that is to say, to be new shingled, weather-boarded, painted, five large Sash Window, Door, flooring, plaistering, and proper Workmanship within; Notice is hereby given, to all such as are willing to undertake the doing thereof, That they offer their Proposals to the Mayor who will inform them more particularly what is to be done.".(Stephenson 1946: 8)

The Corporation of the City of Williamsburg renovated the playhouse for a proper courthouse. However, no contemporary descriptions of the courthouse building after its changes have been found. The courthouse was still standing and in use in 1766, however, when an exhibit of electrical experiments was advertised to be held in the Hustings Court house (Stephenson 1946: 9). The final documentary evidence of its above-ground existence is found on March 23, 1769 when a notice appeared in the Virginia Gazette of the intention to build a new brick courthouse. At the same time the dispensation of "the present court house" and the property on which it stood was mentioned.

The city continued to own this property until 1770. On September 27, 1770, the city conveyed to John Tazewell the land on which the playhouse had stood (Stephenson 1946: 9). It is possible that the playhouse/courthouse may have disappeared at this time, or that another structure had been built in its place. However, the price charged for the property would have been quite steep if there was not some building on it. In any case the Frenchman's map of 1782 shows several buildings in the area, one especially large one to the south, but none where the First Theatre stood. It seems that the playhouse, turned courthouse, had disappeared sometime between March 23, 1769 and the time of the Frenchman's Map in 1782. Figure 1 is the Frenchman's Map, illustrating these buildings. Figure 2 superimposes this map over the excavated foundations of the First Theatre.

On August 1, 1772, Governor Dunmore granted to John Tazewell full control of lots 163, 164, and 169, as Dunmore had come into possession of all the land except the property around the site of the First Theatre. In 1779, the entire property was conveyed by John Tazewell to Henry Tazewell "bounded by Palace Street on the West by the lot of Thomas Everhard on the North by the lots of John Blair, Esq. on the East and by the Market Square on the South." (Stephenson 1946: 10).

Sometime prior to December 17, 1785 the property appears to have come into the control and possession of William Rowsay. (Virginia Gazette, December 17, 1785). In 1788 Edmund Randolph purchased these lots from Rowsay's executors, and on the same 6 date St. George Tucker bought the property, and "houses on the Palace Street," which were on those lots "whereon William Rowsay lately lived."(Tucker Coleman Collection, Research Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation) . The property thus conveyed to St. George Tucker remained in the Tucker family until its purchase by the Williamsburg Restoration.

Archaeological Investigation of the Property

The archaeological examination of Lots 163, 164 and 169 began in the summer season of 1930. A Mr. Mayall, assistant to Arthur Shurtleff, of the Landscape Department was the first to excavate and, according to the 1930 archaeology report, his progress was hindered by a "large and handsome tree" growing in the midst of the foundations.

Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin commented on the quality of that work then he visited the site on June 4, 1930. Finding a crew of laborers at work with no supervision, he noted that "no real care was being taken to look out for bits of china, glass, and other remains of former habitation". He further observed that "In less than five minutes I picked up over a dozen pieces of china and glass, any one of which, under expert examination, might have helped to determine the nature and date of the building or buildings which stood on this foundation." Goodwin, writing to Robert Deane on February 3, 1932, further described the digging as having been done in somewhat of a "piecemeal manner", but believed "we have the material fairly well located" (Goodwin 1932).

The artifacts were described as "the usual fragmentary china, pottery, glass and iron," and specifically mentioned were a considerable quantity of delft tile fragments similar to those excavated at the Palace site. Goodwin also noted that only a small part of the assemblage could be directly related to the theatre. Most represented the activities of the apothecary shop on the lot (Goodwin 1932).

The excavation was incomplete due to the above mentioned tree and the presence of a large above-ground dump. The results were thus inconclusive. Indeed the foundations were described as "rather meagre on the whole" and "scarcely indicated a building that could have been used as a theatre however small it may have been" (Summer Field Report 1930: 12). Trenching took place throughout the immediate area but no walls were found. - The author of the report did speculate that the actual site of the First Theatre might have been found in the immediate area, but a standing garage impeded progress to the east. The trenches-and the excavated foundations of the supposed First Theatre were later backfilled.

7More significant work took place in this area as reported in a memo from H.S. Ragland to H.R. Shurtleff in May 1931. At this time several brick foundations were discovered, of which one was decided to be the First Theatre. Excavation was carried out in the "North West Corner of the St. George Tucker (Coleman) lot on the East side of the Palace Green, about 150 feet, North of Nicholson Street" (Ragland 1931: 1) (see Figures 2 and 3, "originally proposed site of First Theatre").

On Lot 163, facing the Palace Green, two series of foundations were uncovered. One was assumed to be a residence with a central chimney, the other thought to be a more recent small outbuilding. Its walls transected lots 163 and 164, and laid above the other foundations. The central chimney foundation made the use of the structure as a theatre impossible.

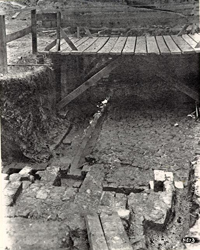

According to Ragland, once Lots 163 and 169 were examined archaeologically, and the located structures were dismissed as possibilities for the First Theatre site, Lot 164 was determined to be the only remaining possibility. He then assumed that the "old walls" located there must be the site of the Playhouse. He concluded that the "walls are very old, for to completely expose them it was necessary to remove a large mulberry tree, estimated by the landscape architect's men to be about 70 or 80 years old, which had grown over the Southeast Corner of the foundation and nearly filled the basement with its roots" (Ragland 1931: 5). Figure 4 depicts these foundations, looking north. In the background stands the above mentioned mulberry tree with the C. M. Hall House behind it.

Ragland also felt that the placement of the foundation walls formed an appropriate plan for a theatre. He further argued that from the documentary evidence it was known that Levingston built only a dwelling house, a play house, a kitchen, and a stable. He was able to eliminate the possibility of it being the stable by the presence of the cellar for "certainly no colonial stable had a cellar" (Ragland 1931: 6).

Examination of the archaeological drawing of May 27, 1931 reveals a structure with dimensions of 40' x 18' with the long end facing the Palace Green (see Figure 3). In addition, several interior walls were bonded to the original exterior wall and evidence of bricking up of doors, etc. was found. Basement entrance steps were also original at the north end of the building. The cellar seems to have been brick paved, with an unusual form of sump pump in the northwest section. Figures 5 and 6 are photographs of the paved cellar and its sump pumps, as well as the brick steps leading to it. A letter from Joseph W. Geddes of Perry, Shaw and Hepburn to the Williamsburg Holding Company indicates that money was approved for "screening the excavated dirt and debris" in "view of the historical importance of the 12 early theatre, through its association with the interests of the citizens of colonial Williamsburg" (Geddes 1931).

In a letter to Robert Deane in January of 1932, Harold B. Shurtleff maintained that the exploration of the Coleman lot was thorough from north to south to a distance of sixty feet in from Palace Street. He did not think it likely that the structure would be found any further east than that point. He noted that the area north of this and adjoining the Coleman property was not examined because a house was still standing at the time of the excavation but had recently been removed. This structure was the C. M. Hall House, a two story frame structure with no basement built around 1895 (see Figure 4). Since this building now had been removed Goodwin conceded that "I suppose the lot could be excavated now, if we felt at all doubtful of our present archaeological evidence for the 'first theatre site' as it stands now" (Shurtleff 1932).

Deane seemed to have further doubts of the evidence of the foundation being the first theatre, and Shurtleff again responds: "Also if the foundations we have uncovered to the north of Gilmer Shop are not the Play House, what on earth are they? We have nothing to explain them with, except the Play House theory."

However, Singleton P. Moorehead and others persisted in urging additional work between the site of the First Theatre and the south fence of the Brush property, and permission was gained nearly 15 years later to work between the planting beds belonging to Mr. George P. Coleman. This work was necessary as that portion of the property had never been excavated and we "were desirous of making this last check to be sure no other structures might occupy position there" (Moorehead 1947).

This work was carried out to the north of this structure (Area G) in the Northwest corner of Colonial Lot 164 in April and May of 1947 by James M. Knight. After initial investigation the planting beds were removed and the entire area was open for investigation. As seen in Figures 2 and 3, a second foundation was uncovered, the southern wall only 91 north from the bulkhead entrance of the previously discussed structure. The remains of this brick foundation measured 30' - 2 ¼" x 22'- 3", with a wall thickness of 13 ½". Figure 7 illustrates the northern wall. The front or west side was approximately one and a half feet from the east line of Spotswood Street. Lying east to west, at approximately two and a half feet north from the center line was a 911 wide partition or crosswall (Figure 8).

Traces of three other brick foundation walls were discovered running parallel to the long side of the structure (north and south). These consisted of fills of brick and mortar fragments, and the first was 18' - 0" from the existing east wall. Additional salvaged cross walls were discovered 37' - 6" and 15 63'-0" from the east existing foundation. If this farthest wall is the rear of an addition or extension to the building that once stood on the brick foundation then the structure would have measured 86' - 6" x 30' - 2 ¼".

It should be noted, however that in recent discussion with James Knight, he cautioned that the interior crosswall was not bonded to the foundation and could be a later addition. He also noted that the outlying walls had been severely robbed and little evidence remained to assure their original state (personal communication, May 16, 1985).

In addition, the remains of five post holes were discovered, each 9" x 9". Four of these were in a line, while one lay some 1' - 6" to the north of the line. Knight noted that if the foundation crosswall was extended to the east, these holes would be just to the north and south side of it, and theorized that these holes were the location of "post or upright timbers placed there to support the ceiling when it began to sag in the center at some later date." (Knight, 1947). These postholes were not excavated, however, and there is no definite evidence that they are related to the structure except the conclusion that such a long ceiling span may have needed additional support.

The artifacts from this area were also predominately related to the activities of an apothecary shop, such as pill cups and small medicine bottles. He reported finding both whole and broken specimens. Thirteen feet east of the brick foundation wall, and almost on the center line, was found a trash pit 10' x 4', "filled with black earth, broken ale bottles, small medicine bottles, pill cups and fragments of eighteenth-century china." (Knight 1947: 3) This was 2' - 6" below grade.

Since Knight found that the existing foundation appeared to have been a discrete unit with all outside walls bonded together, his final conclusion was that there once was a story-and-half brick structure facing the Palace Green. He also suggested that there was a long wooden addition extending to the east, the same width as the brick building.

Several problems can be seen with the interpretation that this was an above ground brick structure. First, there is no conclusive evidence beyond Knight's assertation of its building material. Secondly, the documentary evidence argues against it; the advertisement for repair work on the Play House and renovation into the courthouse calls for it to be "new shingled, weather-boarded, painted," certainly unnecessary repairs to a brick structure, even though they could have been referring to the possible wooden addition (Virginia Gazette, December 16, 1745). (For a further discussion of this wooden addition, see the Conclusion).

16In addition, all models and drawings of the reconstructed building show a frame structure, and Singleton P. Moorehead reports that the excavated walls "were of a thickness usually conventional in Williamsburg as supports for a frame building of the period." (Moorehead n.d.)

In a report dated December 1, 1947 and entitled The First Theatre and its Site: A Summary of Facts Including New Evidence, Singleton P. Moorehead authoritatively discounts the original First Theatre site and presents an "entirely new theory concerning the First Theatre, the Levingston House, Levingston's Kitchen, and the Tucker House itself". He gives a summary of the archaeological and architectural research of the earlier period as well as reporting the more recent archaeological work of James Knight in 1946 and 1947.

He also reported some new documentary evidence discovered concerning the St. George Tucker House and lot. A memorandum for repairs on a structure measuring 40' x 18 ½' for St. George Tucker shows that Tucker was asking the carpenter to estimate the cost and labor of moving a house of that size and to repair a house and several outbuildings. This size corresponds almost exactly with the dimensions of the structure originally thought to be the First Theatre and the dimensions of the core of the current St. George Tucker house. In addition, one of the workmen was advised to salvage and clean as many brick as possible for reuse in the Tucker House, which could certainly explain the missing brick foundation

Moorehead thus put forth his analysis of the available information and made several important new interpretations:

- 1.The structure that had only recently been uncovered was indeed the First Theatre Site. The greater overall size, more appropriate plan, lack of a basement, and other details indicating non-domestic usage "overcome earlier reservations."

- 2.The structure that was originally believed to be the First Theatre site was indeed Levingston's house, later moved by St. George Tucker to the opposite corner and subsequently enlarged and altered (see Figure 9).

- 3.The structure that was originally believed to be Levingston's House was actually Levingston's kitchen.

Several other features were discussed by Moorehead in correspondence in. 1951. He postulated that the piers or posts within the structure excavated in 1946 were of the Courthouse period, and that the pits discovered in the same excavation were perhaps related to privies from the Tucker House establishment after the removal of the Theatre/Courthouse. These pits are most 18 likely those referred to as modern and five feet below grade in the 1947 archaeological drawing.

He also explained the function of the various crosswalls in the context of a working theatre. According to Moorehead, these walls occurred at positions of "considerable significance-- one at the line of the proscenium, one at the bottom of the pit floor and one at the top of the same slope which also represents the front of the main gallery above. "(Moorehead 1951). Unfortunately, no foundation walls were found below the bearing lines of the front of the side boxes and galleries as would be expected. If these had been found, Moorehead felt that "there would be no question whatever ... that we were dealing with the foundations of a proper theatre" (Moorehead 1951a).

The northern portion of Lot 164 were partially uncovered again by Ivor Noel Hume in 1967 in the examination of the Brush-Everard property kitchen property (Figure 10). This limited work began with the removal of the backfilling from the earlier test trenches. The artifacts thus recovered were quite extensive as the previous work had cut through five colonial trash pits. In addition, it was possible to recover artifacts that had retained their provenience through the excavation of the areas between the cross-trenches and in some cases, beneath them. This last is especially important evidence. If the original crosstrenches were not excavated to subsoil, additional information may remain in the other surrounding areas of the First Theatre site.

Noel Hume excavated several of these trash pits, and the majority of artifacts seemed to be related to pharmaceutical equipment dating to circa 1745. However, he notes that due to time limitations not all of them were completely excavated. (For further detail, see The Brush-Everard Kitchen Site Report, 1967).

Also discovered beneath a thin layer of topsoil was a brick chimney foundation with a small section of abutting wall of a presumed pier foundation structure (see Figure 11). He dates the brickwork to approximately 1800 based on a pearlware sherd that lay in the deposited layer directly beneath the foundation, even though he noted it could be much later. This foundation was uncovered in 1947 but had not been mapped in. No attempt was made to identify the owner or function of that structure.

Excavation also continued south of the fence lines and an unusually large amount of pharmaceutical material was also recovered here. Noel Hume suggests that all of this discarded debris was related to George Gilmer, the apothecary who owned Lot 164. As no cross-mends were found between this material and that relating to Lot 165 (the Brush-Everard property) he argues that the fence line between Lots 163 and 164 has been erroneously placed. He further states that it is possible that the five 21 Gilmer pits, dug before 1745, were covered prior to November of that year when Gilmer sold the First Theatre building and six feet of land surrounding it to the city, as these rubbish deposits would have been quite near if not on this public property.

He concludes that the northern portion of Lot 164 held a large quantity of vastly important material "as they contained the largest and earliest closely dated collection of pharmaceuticalia yet excavated in Williamsburg." He also pointed out that the discovery of a robbed colonial wall suggests a need for a thorough re-examination of this property.

Modern disturbance to the area seems to have been quite limited. Figure 12 is a comparison of 19th and 20th century structures with standing or archaeologically excavated structures. As previously noted, the C.M. Hall House stood on the property until 1947 and can be seen on the Sanborn Map of 1931 (Figure 13). The only other structure located in the immediate environs of the First Theatre site in this century was a 14' x 18' one story, frame garage. It is not known when this was removed.

In addition, cartographic and photographic evidence indicates the rebuilding of a "summer house" or "tea house" east of the First Theatre site. A photograph of 1932 taken from the view of the garage shows the building of the "teahouse" and a series of intersecting walkways (Figure 14). The gravel or shell paths may have disturbed the surface to a depth of 6 - 8". The teahouse is also mapped in on Figure 13.

Conclusions

As can be seen from the preceding text, the property upon which the First Theatre originally stood has a complex history, and the previous confusion over the First Theatre site only further muddles the history of the property., Even though recent disturbance has been limited, a number of 18th and 19th century foundations have been uncovered archaeologically, and several others can be seen on map evidence. Many of these are of unidentified function or owner, and are only briefly described or not mentioned in previous archaeological work.

An excellent example of these uninvestigated foundations in the vicinity of the First Theatre is the structure said to be standing in 1800 entitled "Home of Colored Mammy and her Husband" as shown on a 1930 map of the St. George Tucker House. (see Figure 13). This lies just north of the former C. M. Hall house and could perhaps be located in any reinvestigation of the First Theatre property. In light of the Foundation's current 25 and projected interpretative education curricula such a site could be of great interest.

A final point must be that the property in question is located between the Brush-Everard House, an area of intensive study, and the St. George Tucker House, an equally important Williamsburg property. To fully understand these properties, an examination of all foundations on Lots 163, 164, and 169 should be undertaken. Even though the foundations uncovered in 1947 are now accepted as that of the First Theatre, even Moorehead was dismayed at the lack of walls beneath the bearing lines of the side boxes and galleries as would be expected. This planted the smallest seed of doubt in his mind, for if these had been found "there would be no question whatever... that we were dealing with the foundations of a proper theatre." (Moorehead 1951). The certainty with which the 1931 evidence was taken should prove the importance of investigating all possibilities before making any decision about the First Theatre.

More precise modern archaeological techniques may also provide additional clues to the interior and exterior of the building, a problem area admitted by many throughout the decades of discussion concerning this property. Moorehead stressed this several times in his discussion of English theatre precedent, noting "Our evidence is not sufficient to allow us to say that this is what the Theatre of 17-16 was like. We can only say that within the limits of the evidence before us, we can present a typical theatre of the period following the size indicated by the foundations." He further stated "Neither in the... (documents) nor in other known material is to be found specific mention that the structure was a proper theatre--that is, one with conventional pit, boxes, galleries and deep apron stages. Nor do the foundations clear up the issue... If the theatre was not a proper one, no one can say what shape it assumed... "(Moorehead 1952: 6-7).

The reconstruction of the First Theatre could well be aided by the re-excavation of the First Theatre property. This could be accomplished by the recovery of any of a number of architectural materials giving clues about the appearance and usage of the original structure, as well as its renovations and subsequent changes. For instance, it may be possible to date the destruction of the so-called wooden addition, to provide some explanation for the various problems related to pharmaceutical discards beneath it, etc. (See feature sheets for a more detailed discussion of these anomalies.) Also, the architectural and structural elements of a "proper theatre" such as post supports for boxes, galleries, etc. would most likely have been missed in the 1947 cross-trenching.

There is also much we do not know about the usage of the building in several phases. When purchased for use as a public 26 building, it had not been "put to any Use for several years and is now going to decay". Nor do we know its history between the time of the building of the new courthouse and its disappearance. Any structural changes to usage as a dwelling or other building function may be seen.

The problem of course, with the re-excavation of any property in the restored area is the assessment of previous damage both from later buildings and archaeological work. The C. M. Hall house does not seem to have greatly obscured the foundations as discovered in 1947. The areas between the cross-trenches may yet hold significant artifactual and architectural data. In addition, previous re-excavation at other properties such as the Peyton Randolph House shows the importance of even the archaeological finds redeposited by earlier excavators. Photographs of the excavations of this structure shows that interior fill does remain. (See Figure 4). Finally, the surrounding area of the structure has not been totally excavated, and parts of the original Levingston lots have never been fully examined.

The study of this area of Block 29 can provide answers regarding the other standing structures as well. Referring to the area just south of the fence line of the Brush-Everard House, Noel Hume urged "a thorough re-examination of this property" to correct the possible erroneous placement of the boundary. He also pointed out the importance of the material recovered relating to the Gilmer Apothecary Shop, as a very extensive and closely dated collection. As mentioned before, various outbuildings relating to the owners of the three colonial lots may also be discovered, up to and including St. George Tucker.

In conclusion, even though previous archaeological work has been extensive in the area, the potential for the recovery of additional evidence is still quite good. The importance of the First Theatre site itself heightens the significance of any new archaeological information. Its historical significance as the first working theatre in America, its contextual importance for early 18th-century Williamsburg as a visible sign of increasing leisure, wealth, and population, and its interpretive potential for the Foundation's long range growth all combine to make the First Theatre site an excellent candidate for archaeological investigation.

REFERENCES

- 1952

- Architectural Report, St. George Tucker House. Block 29, Building 2, March. Revised from original, August 1933, by Washington Reed, Jr.

- 1967

- Brush-Everard House Kitchen and Surrounding Area. Block 29, Area E. Colonial Lots 164-165. May.

- 1947a

- Archaeological Report, Block 29, Area G. (Northwest Corner of Colonial Lot 164) October 24.

- 1947b

- Brick Size Comparison (First Theatre-St. George Tucker House). November 26.

- 1948

- "The First Williamsburg Theatre". William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Series, V (July), 364-365.

- n. d.

- The First Theatre and its Site: A Summary of Facts Including New Evidence.

- 1952

- The Theatre of 1716, or The First Theatre in British America at Williamsburg Virginia. Special Study, Williamsburg.

- 1931

- Foundations of the First Theatre in America, Williamsburg, Virginia. Memo to H.R. Shurtleff, May 1931.

- 1931

- Archaeology Report on Summer Excavations for Summer Season... 1930. June to September 5.

- 1955

- The Colonial Theatre: Its History and Operations. Volume One. Special Study, Williamsburg.

- 1930

- Colonial Buildings on the Present Coleman Lot, Block 29. October 17.

- 1946

- The First Theatre: Colonial Lots 163, 164, and 169. November. 28

- 1947

- Tucker House, Block 29, Colonial Lots, 163, 164, 169. April.

- 1955

- Dr. Gilmer's Apothecary shop Site (Block 29, Colonial Lot 163). September.

- Joseph W. Geddes to the Williamsburg Holding Company, July 18, 1931.

- Harold R. Shurtleff to Robert Dean, January 29, 1932.

- Robert Dean to Harold R. Shurtleff, February 3, 1932.

- W. A. R. Goodwin to Robert Dean, February 3, 1932.

- Harold R. Shurtleff to Robert Dean, February 23, 1932.

- Helen Bullock, Memorandum. Site of First Theatre. February 16, 1932.

- Singleton P. Moorehead to file, re conversation with George Coleman, February 28, 1947.

- Singleton P. Moorehead to Richard Southern, June 25, 1951. (1951a).

- Singleton P. Moorehead to Ernest Frank, July 27, 1951. (1951b).

- Singleton P. Moorehead to Johnathan W. Curvin, July 28, 1952.

- Mr. Chorley to C.H. Humelsine, Memo, January 3, 1957.

Correspondence:

Feature: First Theatre Site Foundations

Catalogue #: 29-G

Description: Brick foundations measuring 30'-2 ¼" x 22'-3", with wall thickness of 13 ½". Front or west side was approximately 1 ½'from the east line of Spotswood Street. Lying east to west at approximately 2 ½ feet north from the center line was a 9" partition or crosswall. The number of brick courses ranged from one to three. There was no evidence of basement, chimney or entrance steps.

Traces of three other brick foundation walls were discovered running parallel to the long (north/south) axis of the structure. The only remains were brick fragments and shell mortar, the original brick work undoubtedly salvaged. The first wall was at 18'-0" from the existing east wall, the second at 37'-6" and the last at 63' - 0".

If the last of these additional parallel walls is considered the rear of a wooden addition or extension to the building then the building would have measured 86'- 6" x 30' - 2 ¼".

Location: Block 29, Archaeological Area G. South wall beginning 9 feet north of Levingston House basement entry steps; west wall 1 ½' east of Spotswood Street, 53' - 11 ½" from north wall to southern edge of Brush-Everard property (formerly owned by Estelle Smith). (See Figure 3)

Associated Artifacts: "mostly articles from an apothecary shop, such as pill cups and small medicine bottles-both broken and whole ones."

Investigator: James K. Knight

Condition: All walls to the east of the bonded brick foundation have been salvaged. Only portions of complete brick courses remain.

Past Interpretation and Significance: Within months after the completion of the 1947 excavation of this property. the interpretation of this area was drastically altered. With this new evidence, what had previously been considered the First Theatre was now identified as the Levingston House. The plans for reconstruction were similarly changed.

Excavation Technique: According to photographs of the excavation in progress, work at this site seemed to follow standard procedure for the era. Cross-trenches were dug at a 45 degree angle from the street and at five foot intervals. Upon the discovery of foundation walls additional trenches were laid to 30 attempt to follow the outlines of extant brick features. Interior f ill seems to be extant. According to James Knight, no screening was carried out.

Additional Comments: See Archaeological Drawing, Block 29, Area G (June 2, 1947).

- Knight, James. Archaeological Report: Block 29, Northwest Corner of Colonial Lot 164, October 24, 1947.

- Knight, James. Personal Communication. May 16, 1985

- Moorehead, Singleton P. The First Theatre and its Site: A Summary of Facts and New Evidence.

References:

Feature:. First Theatre Site Postholes

Catalogue #: 29-G

Description: Five 9" x 9" square post holes, one containing remains of rotten post. Fill is "black earth".

Location: Beginning 8'-0" east of the western wall of the bonded brick foundations now considered to be the First Theatre Site, and extending east in a roughly straight line. The final post lies 35' - 6" from the eastern wall and contains the rotten post remains. The postholes in between are at a distance of 15'- 6", 22'-0", and 26-0". If a line was extended from the crosswall or partition of the complete foundation, four of these would lie directly to the north and south side of it (See Figure 3).

Associated artifacts: Not applicable.

Investigators: James K. Knight

Condition: The postholes were not excavated in 1947 and should be extant beneath the backfill.

Past Interpretation and Significance: Knight suggested that they were later added as additional support for the ceiling after it began to sag. Morehead adds that they were possibly of the courthouse era.

Excavation Technique: The presence of postholes were discovered by cross-trenching. Knight then shaved the soil down to expose the line of postholes but did not excavate, and his efforts were limited to the area for which postholes are indicated in the archaeological drawing. Therefore, there may well be more postholes in the area which could provide a different interpretation.

Comments: There is little conclusive evidence to support the connection between the First Theatre Site foundations and the line of postholes. Morehead and Knight based their, conclusions on the conviction that such a long span of ceiling would ultimately require support, and that the postholes indicate a later addition of structural timbers. However, as they were not excavated, they could well relate to any structure or even a fence line. Their large size and dark fill, as well as an extant rotting post, raise serious questions as to their age and function. In addition, one of the postholes cuts a large trash pit related to a later occupation than the building of the site. This will be explained in the following section.

Feature: First Theatre Site Trash Pit

Catalogue #: 29-G

Description: Oval pit 11'-0" x 4'-4" in diameter and at 2'-6" depth below grade. A later 9' x 9' square post hole cuts the edge of the pit at approximately 2'-9" north of the baseline.

Location: Western edge of pit lies approximately 12'-6" from the eastern edge of the whole brick foundation. Eastern edge of pit lies 1'-6" south of first robbed wall of wooden addition. The archaeological baseline falls slightly south of the midpoint of the pit (See Figure 3).

Associated Artifacts: According to the archaeological drawing (1947), the feature contains "considerable fill of broken ale bottles, broken and whole pill cups, broken and whole medicine bottles, also china fragments".

Investigator: James Knight

Condition: Unknown

Past Interpretation and Significance: No attempt was made to assess this feature. Its presence and artifact content is found on the archaeological drawing.

Excavation Technique: Unknown.

Additional Comments: Even though no mention of this feature is made in the archaeological reports, it holds special evidence of the history of this structure. The artifactual content seems to suggest the presence of an apothecary somewhere in the vicinity. George Gilmer acquired the property in 1735 and his apothecary shop was on the corner. Noel Hume's excavation of the nearby Brush-Everard property uncovered several similar pits (see later feature sheet) and was able to date the artifacts to approximately 745. This evidence suggests to him that these pits to the north of the First Theatre foundation were closed at the time that Gilmer sold the property to the city.

It is known, then, that trash pits related to the occupation of Gilmer is found in the immediate vicinity, and it seems that this pit is similarly associated. However, the importance of this particular feature found within the foundations of the so-called wooden addition is its relation to the series of postholes which have been interpreted to be structural supports related to the First Theatre or its later use as a Courthouse. One of these postholes cuts through this trash deposit. If the addition was a part of the original First Theatre structure erected in 1716 and remained with it until the structure's complete destruction then the pit would have been placed under 33 the floor of the building. We might assume that this addition was torn down at the time of Gilmer's ownership, except for the presence of the posthole cutting through the trash deposit, and thus a later phenomena. One solution may have been the taking up of the floor in the renovation of the First Theatre into the Courthouse and the filling of a hole with Gilmer-related trash from the area. However, careful re-examination of the area is necessary to untangle the chain of events leading to the deposition of these features.

Feature: Levingston House Foundations (formerly assumed to be the First Theatre)

Catalogue #: 29-A

Description: Brick foundation 40' x 18' with long end facing Palace Green. Several interior walls bonded to the original exterior. Evidence of renovation of structure in the form of bricked up doors, etc. Brick paved basement, with original steps from outside on north end of building.

Location: Block 29, Area A (see Figure 3).

Associated artifacts: "China, glass, iron, etc."

Investigators:

- 1930, Mr. Mayall (Landscape Department)

- 1930, Herbert S. Ragland

- 1947, James K. Knight

Condition: Possible robbed chimney noted by Knight. Some damage to structural foundations because of large tree in area.

Past Interpretation and Significance: Until the removal of the C. M. Hall House directly to the north of this site and excavation of that property, this site was assumed to be the site of the First Theatre. Plans were drawn up for restoration based on this evidence and several maps show this to be the First Theatre itself. It is now thought to be the Levingston House later moved to form the nucleus of the present St. George Tucker House in 1791.

Excavation technique: According to photographs of the 1930 excavations, the site was mostly excavated, including the brick paving of the basement and the external entrance steps to the basement (See Figures 6 and 7).

Additional comments: James Knight noted the presence of a sump pump in the basement of the Levingston House, a feature he had not come across in any of his other excavations.

- Knight, James M. Brick size comparison (First Theatre-St. George Tucker House). November 26, 1947

- Knight, James K. Personal communication, May 16, 1985.

- Ragland, Herbert S. Archaeology Report on Excavations for Summer Season, 1930.

- Ragland, Herbert S. Archaeological Report, (Memo to H.R. Shurtleff, May 1931).

References:

Feature: Trash pit just south of current Brush-Everard Fence Line

Catalogue #: ER 1268L &1268N

Description: 1268L: Large rubbish pit measuring approximately 11'-7" (east-west) by 11'(north-south). 1268L is upper level and consists of light brown loam; 1268N is the lower strata filled is a sandy brown loam.

Location: Beneath and extending west of nineteenth-century foundation, northwest section of lot 164, just south of current Brush-Everard fence line. (see Figure 3).

Associated Artifacts: 1268L: fragments of brown stoneware jars, a single Richard Forte wine bottle seal, more that 169 wine bottle bases. Pharmaceutical equipment, including some 50 delftware drug pots, 14 medical phials, 12 Pyrmont water bottles. These artifacts dated to c. 1745.

1268N: Objects included nearly complete Chinese porcelain bowl and plate, tin plated kitchen utensils, five straight stem wine bottle glasses, approximately 350 wine bottle bases, more than 27 delftware drug pots and 8 pharmaceutical phials.

Investigator: Ivor Noel Hume.

Condition: Not completely excavated. According to the archaeological report "the artifacts from the productive strata were retrieved, leaving a layer of silty clay in situ."

Past Interpretation and Significance: Assumed to be related to the occupation of Blocks 163 and 164 by George Gilmer, and that the pits were possibly closed at the time of the sale of the First Theatre property to the city in 1745.

Excavation Technique: Partially excavated by stratigraphic levels. Artifacts removed.

- Brush-Everard Kitchen and Surrounding Area, Block 29, Area E. Colonial Lots 164 and 165. Report on 1967 Archaeological Excavations.

References:

Feature: Rubbish pits

Catalogue #: ER 1268M and 1268P

Description: Two large rubbish pits filled with brown loam and oyster shells, and containing artifacts dating to circa 1745.

Location: Both pits lay immediately west of ER 1268E and ER 1268F and just south and partially disturbed by a wide and deep modern utility trench. ER 1268M seems to have lain within a natural gully (See Figure 3).

Associated Artifacts: "Apothecary debris", including fragments of delfware drug pots and glass phials.

Investigator: Ivor Noel Hume

Condition: Partially disturbed by modern trench. Mostly excavated.

Past Interpretation and Significance: Assumed to be related to the occupation of the area by George Gilmer.

Excavation Technique: Partially excavated by stratigraphic levels. Artifacts removed.

Feature: Rubbish pit.

Catalogue #s: ER 1265E and ER 1265F

Description: ER 1265E: Thick, disturbed grey loam stratum in the upper part of a large rubbish pit, sealed by topsoil.

ER 1265F: Dark grey loam stratum, beneath ER 1268E within the rubbish pit. Natural gully can be seen in section on the pit's northeast edge.

Location: Just north of the present fence line dividing lots 165 and 164 and on a line south of the present smokehouse on lot 165. This rubbish pit cut through a natural gully (ER 1256R). See Figure 3.

Associated Artifacts Reported: On the bottom of ER 1265F, a human mandible diagnosed by a local physician as an elderly Negroid female was discovered. Also found were a high percentage of pharmaceutical equipment, including more than eight decorated delftware drug pots and ten medicine phials.

Investigator(s): Ivor Noel Hume

Condition: Completely excavated.

Past Interpretation and Significance: Assumed to be related to the occupation of George Gilmer. See previous feature sheets for further discussion of the relation of these trash pits to the location of fence lines, etc.

Excavation Technique: Partially excavated by stratigraphic levels. All artifacts removed.

Feature: Large shallow rubbish pit.

Catalogue #: ER 1268Q

Description: Large shallow rubbish pit filled with hard-packed brown loam.

Location: North of ER 1265E &1265F. Cut by and east of modern utility trench. (See Figure 3).

Associated Artifacts Reported: Wine bottle fragments, circa 1745.

Reported Deposition of Artifacts: Warehouse, Department of Archaeology.

Investigator: Ivor Noel Hume

Condition: Almost totally destroyed by utility trench and modern archaeological cross-trench.

Past Interpretation and Significance: Most likely related to other rubbish pits in the area, assumed to be the debris of George Gilmer.

Excavation Technique: Excavation was limited due to the extensive modern disturbance.

Feature: Brick chimney foundation and part of abutting wall.

Catalogue #: ER 1268K (layer predating construction of brick foundations).

Description: Brick chimney foundation, with a small section of its abutting wall, presumedly the remains of a pier supported structure. Two piers were evidenced north and south of the chimney. ER 1268K is a dark brown loam stratum.

Location: On the eastern edge of ER 1268L and ER 1268M, just west of the modern utility trench and ER 1268Q. (See Figure 3).

Associated Artifacts Reported: Mortar of bricks showed no shell flecks. ER 1268K contained a pearlware sherd dating no earlier than circa 1800.

Investigator: Ivor Noel Hume

Condition: From archaeological photograph 67-DB-845 (Figure 11) four courses of brick remain and seem to be structurally sound.

Past Interpretation and Significance: The pearlware sherd from ER 1268K which immediately predated the construction of the brick chimney dates to c. 1800. The brickwork may date much later. The foundation had been uncovered in a 1947 excavation but no record was kept of its location.